SPOTLIGHT: With “Radio John,” Sam Bush Honors the Songs and Soul of John Hartford

By Stacy Chandler

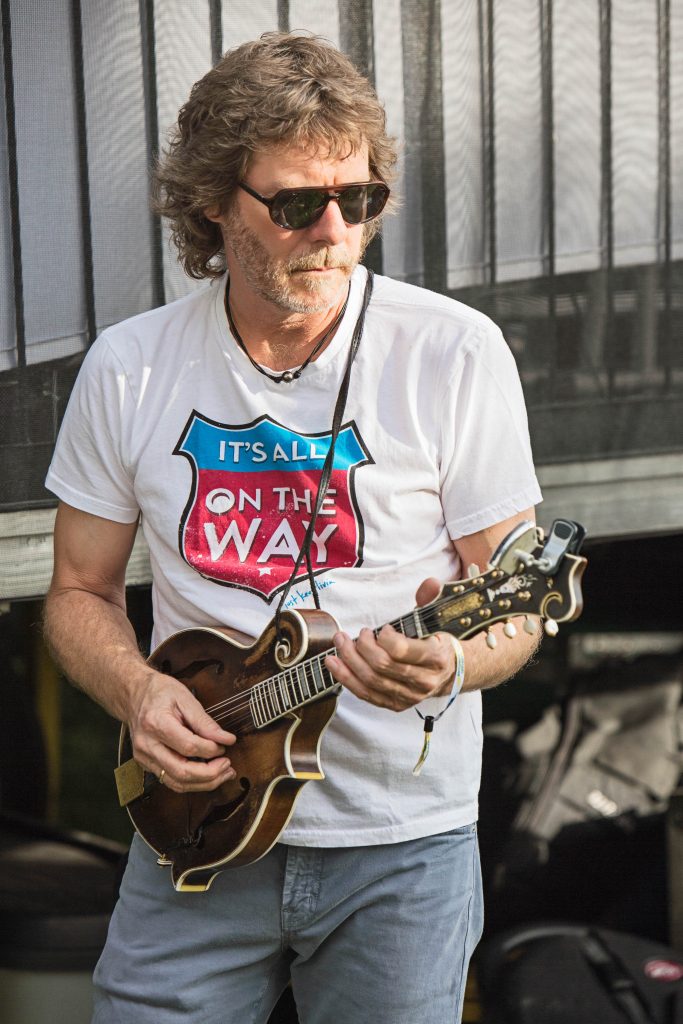

Sam Bush (photo by Jeff Fasano)

EDITOR’S NOTE: Sam Bush is No Depression’s Spotlight artist for November 2022. Look for more about him and his new album, Radio John: Songs of John Hartford, all month long.

Growing up on a farm outside Bowling Green, Kentucky, Sam Bush and his family tuned into a Nashville-based TV station on Saturday afternoons to catch a string of half-hour shows hosted by Grand Ole Opry performers, including Bill Anderson, Porter Wagoner, Ernest Tubb, and Flatt & Scruggs.

One Saturday, on The Wilburn Brothers’ program, one performer in particular caught 13-year-old Bush’s attention.

“A guy came on singing a song but playing Earl Scruggs-style banjo rolls while he sang, and I’d never seen anyone do that,” Bush recalls. The only trouble was, Bush didn’t catch his name.

But a few months later, Bush and his father were visiting Nashville and Bush spotted the man he’d seen on TV on the cover of an album in Ernest Tubb’s record shop. He was finally able to put a face to a name: John Hartford.

Pretty soon, everyone would know Hartford’s name, after Glen Campbell scored a hit with Hartford’s song “Gentle on My Mind” and invited him to play on his own TV showcase, The Glen Campbell Goodtime Hour.

But Bush, just a few years after buying that record in Ernest Tubb’s shop, came to know Hartford first and foremost as a friend.

That friendship, just as much as the music, is what Bush is celebrating with his new album, Radio John: Songs of John Hartford, out Nov. 11 on Smithsonian Folkways.

A Wide Range of Talents

Then just beginning a journey in bluegrass that would credit him with pioneering the progressive “newgrass” musical movement and land him in the International Bluegrass Music Hall of Fame, Bush first met Hartford in 1971 at the storied Bean Blossom Festival in Bean Blossom, Indiana. Bush was playing mandolin with newgrass progenitors The Bluegrass Alliance, and Hartford had brought his band from that year’s groundbreaking Aereo-Plain album.

Sam Bush, left, and John Hartford in an undated photo by Lynn Bush

“We got to meet them, jam some, and discovered that John Hartford loved jamming, maybe more than anyone we’d ever met,” Bush says. They grew closer the more they played together backstage, and eventually, as Bush’s new band New Grass Revival was getting off the ground, they had the same booking agent and manager, so they started playing together onstage as well. New Grass Revival frequently opened for Hartford, and sometimes backed him too. Bush also played on several of Hartford’s recordings over the years.

As a fan, a friend, and a collaborator, Bush knew Hartford’s songs well, and has come back to them throughout his life, even after Hartford’s death in 2001 from cancer. In the last decade or so, he found Hartford’s songs coming with him on his annual winter vacation to Florida, along with the instruments and basic recording equipment he always brings along in case inspiration strikes.

A few years ago, Bush thought he might record a few demos of his favorite Hartford songs to share with his band. But he ran into technical difficulties with his equipment. Luckily, his friend Donnie Sundal, a musician and studio co-owner, lived nearby and was happy to help, bringing his own, professional-grade recording equipment.

“Then it occurred to me, well, maybe I could make this a solo record, because these songs are kind of personal to me,” Bush says. And so he got right to work, singing and recording all the instrumental parts on nine out of 10 songs that would become the Radio John album.

Bush’s primarily instruments, mandolin and fiddle, are present on the album, but guitar also features prominently (Bush calls the instrument “kind of my hobby”) and, being that it’s a Hartford tribute, so does banjo — and Bush plays that, too.

“I used to say I’m a true Southern gentleman: I play banjo, but I don’t tell anyone,” Bush quips with a hearty laugh.

When the pandemic brought Bush’s perpetually heavy touring schedule to a halt, he reckoned it was time to engineer those recordings and finish his Hartford album, but he wanted to add one more song, this one a personal tribute to his friend. Bush wrote “Radio John,” named for Hartford’s moniker from his DJ days at St. Louis station KSTL, over the phone with celebrated songwriter and Alison Krauss and Union Station alum John Pennell during lockdown.

“We came up with a song with like 20 verses,” Bush recalls. “We had to cut it down, but we wanted to write a song about [Hartford] and try to talk about his many talents: the songwriting, the dancing, the singing, the banjo playing, the fiddling, the steamboat captain, the DJ. Pennell and I wanted to make a love song to John, so to speak.”

Bush recorded the song, the album finale, with the Sam Bush Band and a very special guest instrument. The band’s banjo player, Wes Corbett, played a banjo once owned and played by Hartford, on loan from Béla Fleck.

Silly and Sweet

The songs Bush chose to feature on Radio John range from the silly (“Granny Wontcha Smoke Some Marijuana”) to the strikingly sweet (“No End of Love,” “A Simple Thing as Love”). Many were songs Bush recorded with Hartford along the way, and several have resonance that’s just as much personal as professional.

“Morning Bugle,” a twisting melody conveying a happy-go-lucky shrug about not fitting in, was a balm to Bush around Thanksgiving in 1972, when he was on the road with New Grass Revival in Georgia and missing the big family gathering back home in Kentucky for the first time in his life.

“There’s actually a verse about, ‘Gonna get me a place down here for Thanksgiving dinner, don’t ya know.’ And I just remember hearing that song that day — I was kind of homesick, and I just remember it bringing me great comfort,” Bush says. “It’s hard to describe, but the feeling that I get when I either hear the song or sing it, it brings me comfort. So that’s the beauty of music.”

Also especially personal for Bush is his rendition of Hartford’s classic “In Tall Buildings,” a wistful song about growing up and having to close an office door on simple pleasures like sunshine and dew, “goodbye to the flowers / and goodbye to you.” The song, which came out when Bush was a teenager starting to make his way in the world, reminded him of driving toward Nashville or Louisville and seeing their skyscrapers come into view.

“It was more metaphorical for me since I’ve not been an office worker necessarily in a tall building,” Bush says. “But then one day I realized in the ’80s, when we were on Capitol Records, that here I am doing business in a tall building, that I literally moved off the farm and went to work in tall buildings. Not the same way John describes it in the song, perhaps, but that made a mark on me.”

A Good Hang

Through backstage jams and onstage gigs, in the recording studio and even by Hartford’s side as he piloted a steamboat on the Mississippi River, Bush got to know his friend as both a musician and a person.

“He could be one of the most intense, serious people I knew, or, on the other hand, be one of the goofiest guys I ever hung with,” Bush recalls. “By hanging with him, I was exposed to different types of music. We were friends, and we didn’t always agree —so, you know, he wasn’t Saint John to me. He was my buddy that, we had our disagreements, and he’d give me some advice sometimes, and some of it I took and some of it I didn’t.”

Over the years, Bush saw Hartford change again and again, from completely revamping his handwriting to deciding to start dancing as he played music. As he got older he also shifted from devouring progressive music and “jazzy stuff,” Bush says, to a passion for old-time fiddle music.

Whatever Hartford did, Bush recalls, he did it all the way. Far from a quick phase, he poured his soul and a ton of work into becoming a steamboat captain, with the river remaining a touchstone his whole life. And as fiddle tunes moved into his musical spotlight, he learned to read music so he could write out what he heard from other players and recordings as well as transmit his own compositions. He applied just as much energy to being a friend.

“When I was sick with cancer in 1982, John had been through a bout of it already, and he was a good person to advise me and a good coach for me to just keep me up and running and helping me out,” Bush says. “We both believed that the greatest thing we could do to fight cancer is to laugh as much as we could.”

Even as the songs of Radio John highlight Hartford’s musical range and one-of-a-kind turns of phrase, the project honors the man, too, and a friendship that thrived onstage and off.

“We had a lot of great times,” Bush says. “We disagreed, but yeah, I loved him.”