James McMurtry — More Journalist Than Autobiographer

James McMurtry has been known to refer to himself as a “beer salesman.” His job is to draw people to bars and clubs and midsize venues that book him and his band. He puts on a show. If people want to dance, that’s all right. They might get thirsty and drink more.

An album is something to sell on a merch table, like a T-shirt. A souvenir of an experience, not the experience itself.

There’s not much money in them anymore. They’re a part of his business, but not the biggest part. Some people still buy physical product — vinyl records and CDs — but for most of them, that’s a way of signaling support for the artist and the local record stores.

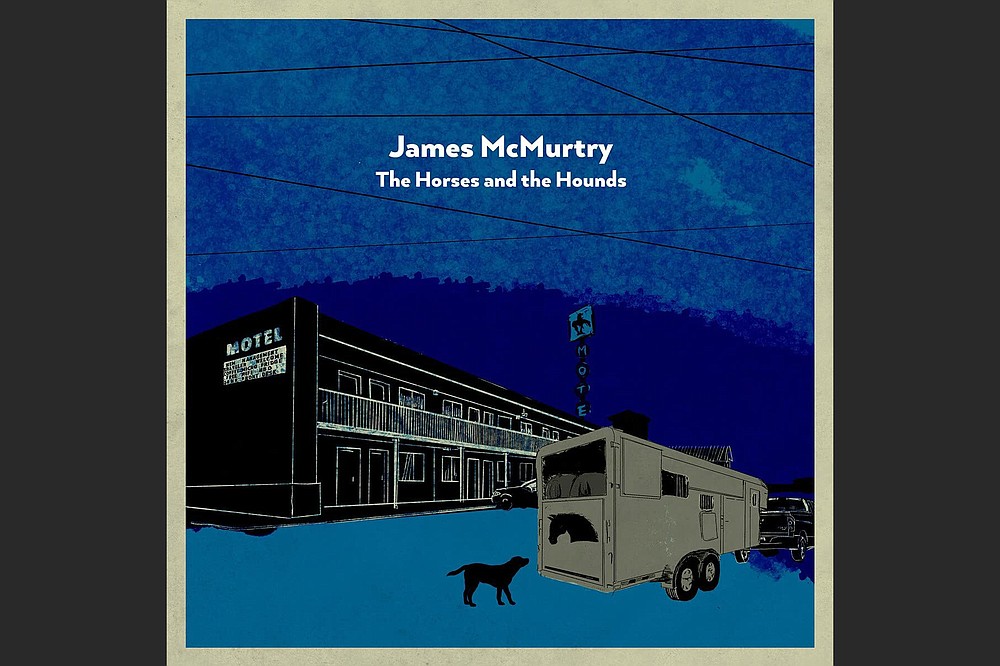

If you want to hear the latest album from almost anyone, all you have to do is tap your favorite digital subscription service — Spotify, Apple Music, Amazon, what have you — then type and swipe. There it is: “The Horses and the Hounds.”

If you have been waiting almost seven years to hear the new James McMurtry record, you can exhale now. “The Horses and the Hounds” is a worthy successor to “Complicated Game” and may even be a better work of art. It’s only been out since Aug. 20, and I’m still not finished with “Complicated Game.” I play the whole recording a couple of times a month and still hear new things in it.

I’ve barely scratched the surface on “The Horses and the Hounds,” but the conventions of my business say I’m pushing the expiration date for a story about it, so I’d better get something down now.

It’s a straightforward country rock record, leaning toward rock, with smart lyrics sung by a confident deadpan baritone, a white dude pushing 60. It’s all story songs and acoustic guitars and deeply conservative in the ways it means to deliver its emotional cargo. It opens with “Canola Fields,” with the wonderful line:

I was thinking ’bout you crossin’ Southern Alberta

Canola fields on a July day

Are about the same chartreuse

as that ’69 bug

You used to drive around San Jose

McMurtry isn’t a novelist like his famous father, the late Larry McMurtry, but his lyrics have something of the observational precision of a novelist and the compression of poetry.

A song lyric should be evocative, but should also sound like something somebody would actually say. Bad lyrics result when someone tries to force a rhyme or goes deaf to meter. This happens to even the best lyricists — as when in Jackson Browne’s otherwise immaculate song “The Pretender” he sings “the children solemnly wait for the ice cream vendor” or when Bruce Springsteen wrote “Secret Garden” — but it never seems to happen to McMurtry. He’s extraordinarily disciplined in a way that suggests he counts syllables sometimes.

A good lyric doesn’t neces- sarily have to tell a story. A lot of songwriters use words more as sonic values than as vessels of meaning haunted by connotation and allusion, but McMurtry may be the best at putting us in the head of a character caught up in a particular human drama.

You get through one of his five-minute songs like “Carlisle’s Haul” off “Complicated Game,” and you feel like you’d read a book about these characters, if you haven’t lived out their lives.

“Canola Fields” is about a certain kind of nostalgia, a second chance with someone you probably should have gotten with in the wayback, except that, if you had, it probably wouldn’t have worked given how complicated everyone’s life was back then. It’s about “cashing in on a 30-year crush” and how you “can’t be young and do that.”

Maybe you can’t be young and write that either, though one thing that McMurtry would tell you about his songwriting process is that he’s not confessional. He’s more a new journalist looking for specific revealing details about the people he’s interested in enough to write about; people who seem to be flown-over Americans — working-class to upper-middle-class denizens of small towns and small cities removed from our cultural coastal elite centers. That’s his work, not his biography. McMurtry’s characters think their own thoughts; it would be a mistake to confuse them with the artist. “The Horses and the Hounds” is the latest album released by James McMurtry.

“The Horses and the Hounds” is the latest album released by James McMurtry.

THE SONG, NOT THE SINGER

I interviewed McMurtry once. The session wasn’t a debacle, but wasn’t satisfying for either one of us. It can’t be easy giving 100 interviews a year to journalists who are either trying to knock out a quick preview or convince their subject that they’re somehow different from every other writer who has asked them questions that could be easily answered by checking the clips.

If you try to press him to talk about his songwriting process, he’ll tell you he’ll hear a line in his head, and if it sticks there he’ll try to figure out who might have said it and why. And that might lead to a song. He used to type bits of lyrics out on his phone, in the notes application, in the comic sans font.

He writes the melody and the lyrics at the same time, then goes back and does the chords.

I tried to get him to talk about his guitars and guitar playing and how he achieves his live sound, figuring that since everyone else asked him about his dad and his songwriting he might warm to a discussion about tools. Even though he’s a really good player with an interesting style, the rig-rundown guitar talk strategy didn’t go anywhere. He was cordial and professional, but steered the conversation back to his talking points, the same way any media-savvy actor might.

(McMurtry has an acting resume — his turn as precocious preteen Randolph in Peter Bogdanovich’s 1974 version of “Daisy Miller” is choice. When a would-be suitor asks young Randolph if he knows the title character — played by Cybill Shepherd — he deadpans, “I don’t know her. She’s my sister.” He also played a cowboy in the 1989 miniseries “Lonesome Dove,” based on his father’s epic Western novel.)

Yet there’s very little about McMurtry that presents as show-bizzy. Some might take his characteristic laconic mien as shtick, but if you were reared in Texas you’ll probably accept it as authentic. Lots of guys walk around in those parts wearing trucker caps and talking slow.

Just because McMurtry attended Woodberry Forest School, an exclusive all-boys private academy in Virginia where he was a classmate of Marvin Bush, the younger brother of George W. Bush (whose administration he railed against on his 2008 album “Just Us Kids”), that doesn’t mean he’s a preppie.

Or maybe we should take notice of the fact that even the dullest of us contain multitudes. As Katharine Hepburn put it in “The Philadelphia Story,” the time to make up your mind about someone is never.

Trust the art, not the artist, and certainly not the artist’s publicist or Wikipedia page. James McMurtry (courtesy James McMurtry)

James McMurtry (courtesy James McMurtry)

WHERE DID YOU HIDE THE BODY?

I came to McMurtry relatively late.

I still remember getting a promo copy — a vinyl album — of his debut album, “Too Long in the Wasteland,” in 1989. Columbia put some muscle behind that effort, produced by John Mellencamp, who had engaged Larry McMurtry to write a screenplay for “Falling From Grace,” a movie Mellencamp produced and directed at the height of his commercial success.

In 1987, the senior McMurtry gave Mellencamp a tape of his son’s songs, and Mellencamp was impressed. He called up the kid and asked him if he could write more. McMurtry said sure, and they went into a studio and made “Wasteland.”

“Hey, if it wasn’t for Dad’s connections, I wouldn’t have made it anywhere,” McMurtry told Phoenix New Times in 1992. “It’s really that simple.”

“Wasteland” could have been taken for the work of a dilettante, an erudite rich boy in a work shirt, doing his best to get out from under the nimbus of Daddy’s reputation and money, and if he’d given up after a try or two and moved on to a career in academia or whatever, well, maybe that would have been fair criticism. (For the record, Larry gave his son a guitar, but James credits his English-professor mother with showing him his first chords.)

His second record on Columbia, “Candyland,” was better, but didn’t chart. I stopped paying attention after that, though occasionally one of McMurtry’s songs would break through. But it wasn’t until the 21st century and I saw him in a small club that I became a fan.

And even then I kept a little mental index card on Mc- Murtry that consigned him to a genre I think of as NPR Music (an admittedly dismissive rubric, though some of my favorite artists reside beneath it): a clever lyricist and a songwriter in the Woody Guthrie-Bob Dylan tradition who is a little too sensitive to critical evaluations that focus on his literary facility while downplaying his musicality.

That was a misconception. McMurtry was more interested in playing guitar than anything else while he was at the University of Arizona in Tucson in the early ’80s; he wanted to be Norman Blake or Doc Watson, a great flat-picker.

But his songs were what people paid attention to and what led him back to Texas and the Kerrville Folk Festival, where he was one of six winners in 1987. Even without his father’s connections, he might have carved out the kind of career he’s had, where he sells a reliable number of units and plays just about as often as he wants.

Or at least he did, until covid-19.

There are a couple of other songs on “The Horses and the Hounds” that rip me up.

One of them, “Jackie,” is an icy violin-driven waltz about a ill-fated horsewoman who drives a truck to make ends meet. Her credo:

I just got two rules, if my

conscience be known

Don’t lie to me, don’t bring

me nothing home

Faithful’s a nice word in

Sunday school class

Life’s just too crazy for that

It’s heartbreaking, spare and offhand and beautifully sung in the rough but shaken voice of a bereaved friend.

Then there’s “Ft. Walton Wake-Up Call,” a spoke-sung cousin to McMurtry’s best known-song, the crystal methamphetamine travelog “Choctaw Bingo.” Here our hero and the woman he must feed are trapped in a particular circle of hell — a Florida beach motel on a 30-degree day.

They need to get back to Atlanta but the airports are socked in by the weather and the rental car has a flat and our protagonist — who feels guilty for having snapped at the desk clerk — keeps losing his glasses.

While McMurtry is not big on the verse-chorus-bridge formula approach to songwriting — he once offered the opinion that choruses ought to be outlawed — here he’s hit the jackpot. “I keep losing my glasses” is the year’s biggest ear worm for me.

If that’s not a conventional sort of record review — I was once told that a record review should be no more than seven column inches long — I guess I’m sorry. “Complicated Game” is one of the better albums of the past decade (a time when the cultural currency of the album has decreased), and “The Horses and the Hounds” can hang with it. I hope it’s not another seven years before we find out if McMurtry is going to return to the mean or continue at this new level.

For all his talk of being a beer salesman, McMurtry is acting like this archaic form still matters.