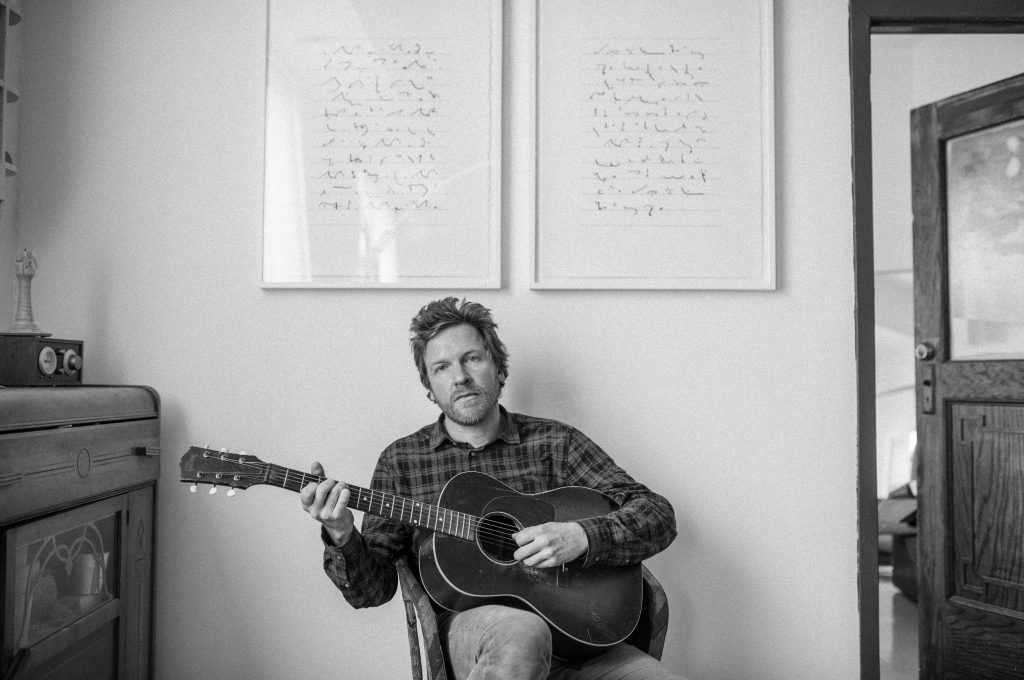

Gentle-Voiced Songwriter Doug Paisley Gracefully Navigates the Intersection of Folk-Rock and Country

Starter Home

7.7

Gracefully navigating the intersection of folk-rock and country, the gentle-voiced songwriter turns detailed images of domestic tranquility and promise into reflections on disappointment.

By Amanda Wicks

For a decade, Canadian singer/songwriter Doug Paisley has turned quiet, specific moments into inquiries on life’s larger struggles. On his 2010 breakthrough, Constant Companion, Paisley used the inevitability of endings to explore understanding oneself, the only possible “constant companion.” For 2014’s Strong Feelings, he mulled death and its uneasy relationship with life, or how their juxtaposition ripples into every wave of existence. And now, on his fourth album, Starter Home, Paisley details the chasm that separates what poet Seamus Heaney described as “getting started” and “getting started again.” These songs examine how the person you are never truly aligns with the person you want to be, especially when you stumble upon a sticking point that’s hard to move past.

Paisley knows the subject well: As he told Exclaim, Starter Home required that he begin again (and again), ultimately recording at four different studios, including those of Cowboy Junkies’ Peter Moore and acclaimed folk musician Ken Whiteley. The results grace his earlier alt-country sound with softer folk touches, putting him in the realm of Kris Kristofferson or even Canadian predecessor Gordon Lightfoot. Paisley understands that personal lyrics don’t have to read like a diary excerpt—that specificity creates universality.

At the start, for instance, he details a young couple’s starter home. “Bring your dreams and your family,” he sings like the real estate sign out front reads, signaling the potential of this simple, scrappy beginning. “Maybe in time we should’ve moved on,” he offers during the closing verse, his voice dimming with quiet reflection. Michael Eckert’s pedal steel adds a wistful glow to the moment’s frayed introspection.

Paisley uses the language of physical space to communicate interior spaces. He stitches needlework scenes that sit uneasily in embroidery hoops—quaint on the surface, a shadow cast across the sides. Despite the jaunty country inflection of “Mister Wrong,” his voice darkens ever so slightly, his cadence quickening as he enumerates the ways he’s going to disappoint. “A home and family, vacation by the sea/On the Christmas tree, I’ll only let you down,” he sings, his voice gasping during “I’ll,” the confession giving him pause. Make enough promises, and more than a few will go broken. The sentiment arises, too, on “Waiting,” where Paisley resigns himself to a similar fate. Expectations can become chokeholds, so “This Loneliness” looks at them askance, as if the past were a mirror Paisley must confront reluctantly. Jennifer Castle adds stark backing harmonies here, her voice rounding out his. But there’s a note of hesitation in the way Paisley sings, an expression of his misgivings about what should have been.

In the poem “I Hear the Traffic,” Leonard Cohen writes, “Another day/To rise and fall/Make a buck/Start and stall.” He lets the final word hang, something to be overcome. If there’s a sense that stalling is fatalistic, Paisley overcomes it. “I look out my window, there’s so many ways it can go/There’s no way to know,” he sings at one point, repeating that last bit again and again, turning it over until it becomes a mantra with its own rhythm. Ultimately, that’s what stalling reveals, Paisley suggests: There’s no rhythm, no living, without the pause.