Frank Black Talks ‘Revenge Tour,’ ‘Teenager of the Year’ Anniversary

Thirty years after the release of his “big, pompous” second solo album, Pixies frontman is reviving his solo career to give it its due, finally

By Kory Grow

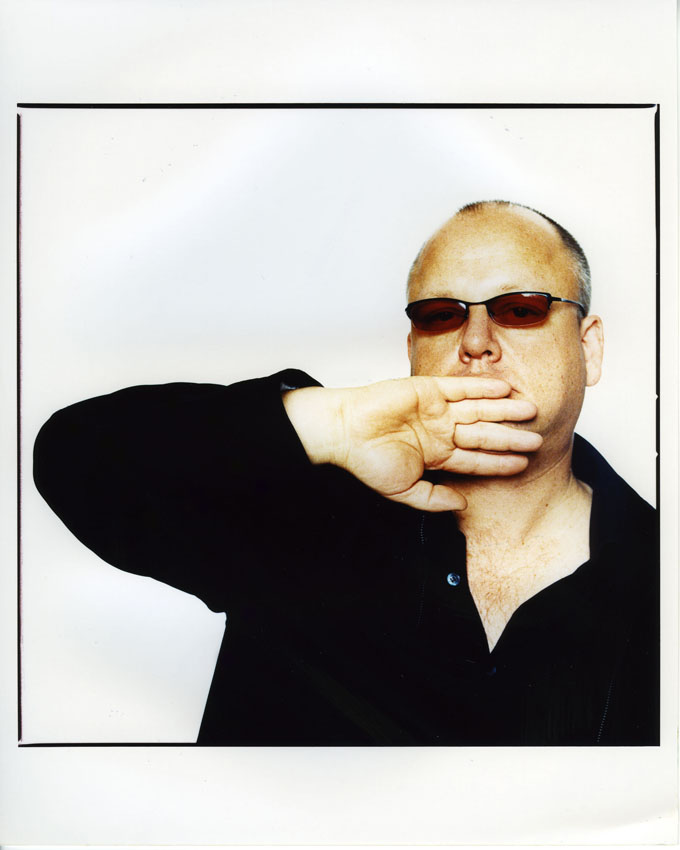

In the early Eighties, Charles Thompson was such a swell, upstanding, likable young man that his high school teachers recognized him with “a funny little dinky award” declaring him “Teenager of the Year.” “I wasn’t that great at school, but they liked me,” Thompson, who’s better known as Pixies frontman Black Francis or as the solo artist Frank Black, says over Zoom. The bespectacled singer is relaxing in his Massachusetts home’s book nook in a blue collared shirt, sipping a nonalcoholic beer, which he switched to about five years ago. “They said, ‘Yeah, you’re Teenager of the Year, there’s your award and you get 50 bucks towards books if you go to college.’ My mom still has the little medallion that I received framed. My brother got the same award the following year.”

Years later, while brainstorming a title for the follow-up album to his first solo record, Frank Black, Thompson remembered the achievement. It was 1994, a year after he blew up the Pixies, and the record was his most ambitious to date: 63 minutes of catchy pop-rock (the single “Headache”), proggy post-punk (“Olé Mulholland”), reggae (“Fiddle Riddle”), and sheer giddy chaos (possibly his greatest solo song, “Thalassocracy”). “There was a kind of indulgence woven into it,” Thompson says, looking back. “I forgive the indulgences now because that was the worldview at the time with me and [co-producer] Eric [Drew Feldman]: We’re going to make it bigger, badder, and fatter just because we want to.” He decided to give the record an honorific worthy of his ambition: Teenager of the Year.

Thompson even recalls how the title dawned on him, fading in with cinematic flair: “There I was in my comfy Cadillac, me and the ghost of [Los Angeles civil engineer] Will Mulholland…” He pauses dramatically. “And Teenager of the Year, it shall be called,” he adds, laughing. “It’s like, ‘This is my pompous moment, man, so I’m going to own it. Yes, yes, I’m pompous. Yes, I’m indulgent. Yes, yes.’ I said yes to all of it.”

The album, which he co-produced with Feldman (Captain Beefheart, Pere Ubu) and erstwhile Pixies engineer Al Clay, came out in 1994. Other than a handful of festival dates, a run opening for Ramones, and some concerts Thompson played completely solo, he feels he wasn’t able to give the album its due when it came out. He feels his label at the time didn’t know what to do with him.

A decade ago, Thompson’s inner circle floated the idea past him to do a 20th anniversary tour for the album, playing it in full, but he was busy with the reunited Pixies, and Feldman and the other musicians on Teenager of the Year had their own commitments. When the record label 4AD recently approached Thompson about remastering the album for a reissue — slated to come out Jan. 17 — that’s when it all really hit him. “Oh, my God: 30 years,” Thompson, 59, sputters. “How many more years are we even going to be able to tour? If we’re going to do an anniversary tour, we need to do it and let’s just do it.”

So he reconnected with Feldman and other musicians who recorded the album with him and booked a Teenager of the Year tour for early next year ahead of Pixies’ European tour. The Teenager of the Year gigs will be his first solo concerts in years, and Thompson figures it will be a good time. “I noticed my fans kind of gather around that record in a different way than they do all the other records,” he says. “So I’m not going to fight it. If people see it as my grand statement, great. I’ll take it.”

Eight years ago, you said you were done with your solo career. Why is it now back on?

I have a big family. I’ve got a lot of kids. A few years ago, it was sort of like, “Well, I could go on a Pixies tour and make money and take care of business, so I’m not going to go do [a solo] tour just because ‘I’m an artist.’” It felt too selfish or something as far as my family were concerned. My kids are older now; they’re grown up and they’re going away to college, so it’s not so much pressure to be at home all the time for them.

I haven’t done any solo shows in six or seven years. But now it’s not quite so important to bring home the bacon, if you will. We can relax into our artistry a little more than maybe we were a few seasons ago.

Aside from the anniversary, what makes Teenager of the Year special to you? Why tour on that one and not, say, Frank Black or Frank Black and the Catholics’ Devil’s Workshop?

Not only is it arguably the most eclectic record of my solo repertoire, but it’s the longest one. It’s the big, pompous one. It’s the one we spent a little too much money on. It’s the one that we went down the rabbit hole with. And for the people that are fans who appreciate the wavelength of the record, that’s the one that they go to. They go, “Oh, yeah. This has a deep, funky flavor that’s, like, the real essence of Charles.”

This one just feels more of a journey [than other records] and it feels very rooted in my California aspects of my life. I’ve gone back and forth between New England and California my whole life. And this was at one of those seasons where I was living in California. It has a lot of wildfires and earthquakes in it. We had to stop recording at one point because of earthquakes.

Did you like living in California?

When I first moved there in about 1989 or ’90, I didn’t want to. I was living in Boston. My first wife wanted to move to California. So we go to California, even though I resisted it. Once you accept something, then you start to get into it. That whole state is just full of stuff: people and history and long roads. And I was in a space where I was really accepting it.

I had my big old Cadillac out there. I lived in L.A., and I just hung out. I wasn’t a rich man, but I didn’t have any kids, and I could do whatever the hell I wanted to do. I could stay up as late as I wanted. If I wanted to do some fucking lame-ass reggae song, then I’m going to do that. There’s a song on there called “Freedom Rock.” That really spells it out: [the album] was “freedom rock.”

Not just freedom rock: You’ve got your reggae song, “Fiddle Riddle,” and you’ve got “Olé Mulholland,” which felt like an homage to Joy Division with its lead bass line. Where was your head at with songwriting then?

I read an interview years ago with Beck who said that every song is its own country with its own customs — its culture. When I read that, I was like, “Yeah. That’s exactly how it is for me, too.” Every song that I do, you don’t know what the rules are exactly, but there’s a culture there.

I think I wanted to sing “Fiddle Riddle” in a lovers rock, UB40 way — almost a falsetto, R&B voice. I knew that’s where the song had to go. I don’t know why. With “Olé Mulholland,” I was worried that it sounded geeky, mostly because thinking about the libretto. I was thinking about William Mulholland and the water. Who do I think I am? Roman Polanski shooting Chinatown? It’s a little geeky, but once you embrace the geography of a place, you start to get into the stories of the past, the ghosts of the place. There was a book called City of Quartz that came out about that time by a writer [Mike Davis] who wrote about the history of contemporary 20th-century California. I read it and enjoyed it.

The lyrics on Teenager of the Year are all over the place. You sing about California, you name-check A Wrinkle in Time on “Headache,” and there are references to the video game Pong and The Three Stooges. Where did all of that come from?

The internet was really this kind of vague, abstract thing that occurred over at AOL.com at the time. So I found what I needed in the esoterica of books that I stumbled upon, sometimes just weird little history things that I stumbled onto in my travels around California.

Was it easy coming up with the lyrics?

I was not writing a lot of lyrics at the beginning of Teenager of the Year. I was coming up with lots of music, but I was going through some writer’s block. I remember Al was living at my house, and Eric was over at his parents’ house, and they were getting concerned about the fact that I hadn’t sung yet on some songs. We were a month deep into this record, and there are barely any words from me. So we had the weekend off and on Monday morning, Eric said, “Al and I sat down and wrote some temporary lyrics for you to fool around with just to get the juices flowing. No pressure. You could use them if you want.” I was like, “Oh, OK. All right.”

And I opened up this thing they typed up for me, and I was completely horrified. I was just like, “What? You think I’m some kind of a UFO nut weirdo? You just kind of dumbed me down and reduced me to this cliché of myself.” I was so offended. … Not really, but that was my visceral reaction to it. I was just like, “Oh, my God. I won’t sing a single syllable of this crap. It’s just stupid.” I was probably a little embarrassed, too, that it had come to this, but it definitely kicked me in the pants. I was just like, “Fine. Fuck you guys. I’ll be there tonight with the fucking lyrics.”

I drove up into the Malibu Hills and pulled over in my car and pulled out my notebook. Before I would go to the studio, I would just say, “Well, they’re expecting the next song tonight, so just fucking do it, Charles, you got no choice. It’s now or never, do or die.” I was under some pressure because I was moved by my hurt feelings.

So I just wrote a song like, “Whatever Happened to Pong?” Like, yeah, this is a song about the first video game, called Pong, because me and my brother used to play it at my father’s bar. We were the first kids to play Pong ever in a bar in Cape Cod.

What about “Thalassocracy”? And what does the concept of “thalassocracy” mean to you?

I had a dictionary of obscure and odd words. I loved the word so I said, “Well, that shall be the title of my next ditty.” And in my own manic caffeinated brain, I just kind of tried to connect the dots somehow and just start writing things that occurred to me. So one minute I’m writing about a video game, the next minute I’m using an old Greek word that talks about a government that rules at sea.

I just was like, “No, I’m going to do whatever I want and I’m going to prove to everybody that I’m ‘Black Francis,’ ‘Frank Black,’ or whatever the hell I am. I can do it and fuck you all. The Pixies broke up, but it’s OK. I still have something to say. I still am valid.” So I didn’t have the time to really question whatever the hell it was I happened to be singing about on any particular day.

Did you really worry that you’d lost the magic?

Every single record that I make is like that, at least until you start getting a little validation from people in some form. It feels really embarrassing, and it feels like, “No, I lost it.” These feelings haunt you until you come up with that first lyric and then that second lyric, and then it starts to kind of flow.

Certainly more than most of my records, there was a lot of desperation on Teenager, a lot of trying to prove myself, a lot of manic energy, a lot of cockiness but also fear of failure at the same time.

Maybe you can work through some of that by playing it live 30 years later.

Everyone’s really excited about it. We weren’t able to do that much touring when the album came out originally. I wasn’t worth a lot as “Frank Black” in the market. I existed, but it was nothing like the Pixies, and so, financially, it was hard for me to pull off.

Unfortunately, we did very few shows around Teenager of the Year. We did one tour opening up for the Ramones for about six weeks. It’s like the sound of one hand clapping if you’re opening up for the Ramones, because nobody is there to see you; they’re there to see the Ramones, including me. After that, I had to break up the band as it were, and just do it on my own.

I’d like to think that maybe next year when we play a few shows, it will kind of be a little bit of a revenge tour.