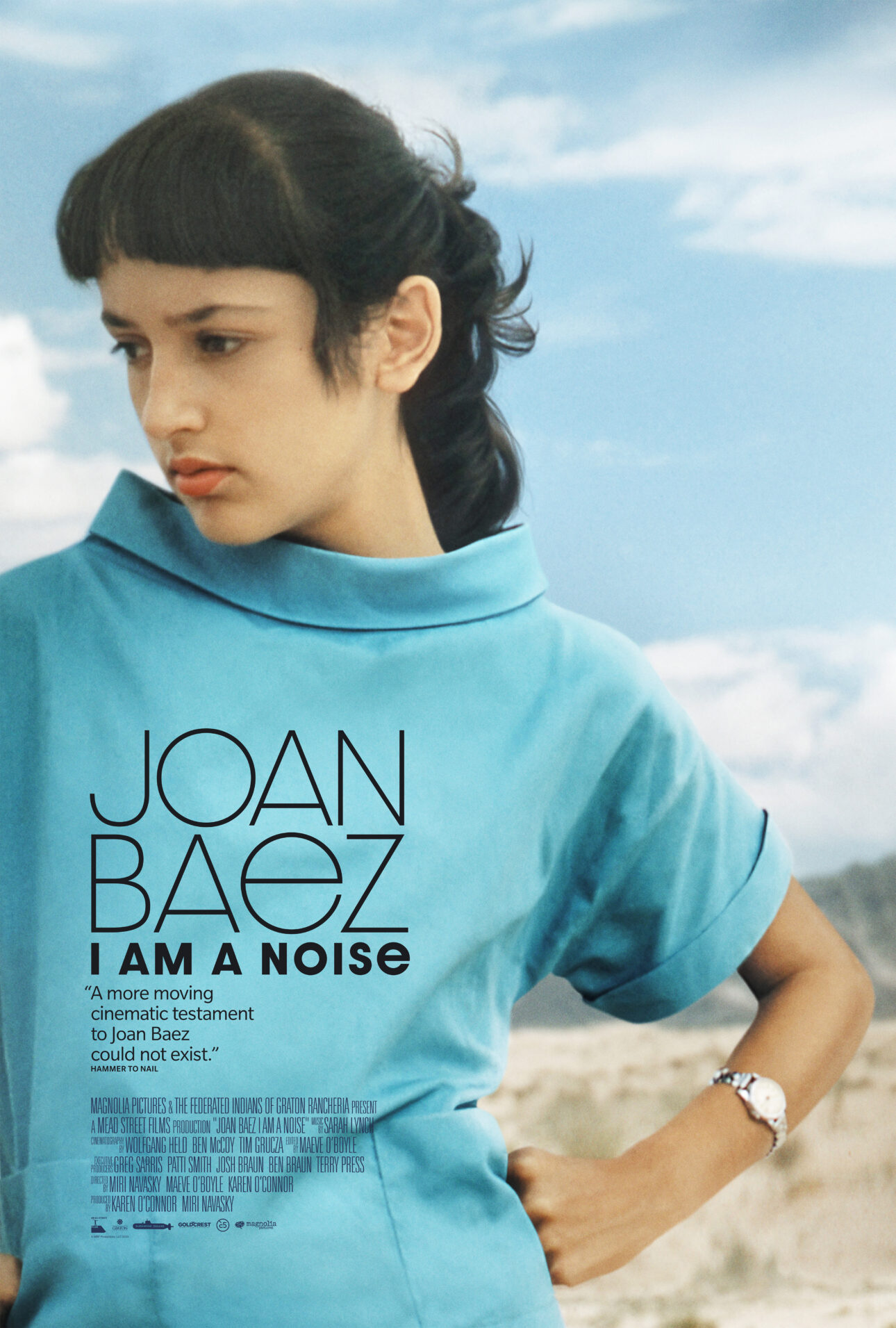

Joan Baez On Dylan, Activism & Living An ‘Extraordinary Life’

[Spin]

We spoke with the 82-year-old musician about her new documentary, ’Joan Baez: I Am a Noise’

Written by Lily Moayeri

Before Nina Simone, before Aretha Franklin, before Bob Dylan and the Beatles, there was Joan Baez. With a big voice and an even bigger presence, from the age of 18, Baez left a mark on the world through her music and her activism. Now, at 82, the definitive documentary, Joan Baez: I Am a Noise delves not only into Baez’s public persona and impact, but deep into her personal demons which range from mental health and intimacy issues to addiction and abuse.

Joan Baez: I Am a Noise is told in cinéma vérité style and avoids chronological storytelling. It began as a concert film documenting Baez’s final tour in 2019. But once Baez let the filmmakers, including co-director Karen O’Connor—a close friend of Baez’s since 1989—into her storage space (read: the Baez family vault), Joan Baez: I Am a Noise took a different turn. O’Connor and her fellow directors Miri Navasky and Maeve O’Boyle uncovered a treasure trove of archival images and footage, as well as audio tapes of Baez’s very private therapy sessions, plus answering machine and voicemail messages from her now departed family.

With this amount of singular content, Joan Baez: I Am a Noise bypasses the talking-heads style of documentary, with the exception of Baez herself. Instead, the narrative is weaved together from primary-source material that traces Baez, her two sisters and her parents from the nascence of their family. It shows Baez at her first sparsely-attended performance to her meteoric rise, literally the following week. Baez at the March on Washington. Baez with her then-boyfriend “Bobby” Dylan—a flirty, smirking version of him rarely seen before, his grin from ear-to-ear when he looks at her, Baez pregnant while her husband activist David Harris is in jail. Baez passed out on quaaludes on her tour bus.

The most jarring parts of Joan Baez: I Am a Noise are when Baez and her sisters’ abuse is revealed through firsthand accounts. Baez’s characterful illustrations outline the experience and her healing process.

More current footage shows sold-out gigs and a still-powerful on-stage presence. Backstage is filled with long-time fans and recognizable faces, among them, Bill and Hillary Clinton. At home, Baez keeps her body and voice in enviable shape with regular exercise. And she is at peace with herself and her demons—even if Joan Baez: I Am a Noise is pushing her to revisit some of the most painful aspects of her life. As she says when she speaks to SPIN, “I put a limit on what I’m going to talk about.”

What pushed you to share your experiences in such an intimate, revealing way?

I’ve known one of the directors, Karen O’Connor, for years. We’re good friends and I know her work. We’ve talked about it periodically for a decade. Then it was, “Okay, we’ll film the last tour. What does a 79-year-old woman do at the end of this extraordinary life touring and the music and so on.” That’s how we started.

In the middle of everything, I gave them a key to my storage unit. I had never been there. In the film when I walk in is the first time I’d ever been there. I had no idea the extent of the stuff that was in there. It’s a director’s dream. It’s also a nightmare, because there was so much stuff. From my father’s great pictures of us when we were two and three years old to my delving into the therapy that gave me a life as a whole person. They edited, literally, for years.

My family is all gone. I couldn’t have done the delicate parts of this if my parents or my sisters were still here. Some of the sister stuff I learned, I don’t know if they’d ever be able to tell me how they really felt. It’s too difficult. I learned a lot.

The storage unit—which looks extremely organized—was holding not just your belongings but that of your family. Were you aware of its contents?

All those therapy tapes I knew were there. I didn’t know they were put in order like that. Probably my assistant and then the film crew did that. I didn’t know about the letters and the early stuff and the letter from the doctor and the footage of us when we were little. Some of it I had never seen before. It was a lifelong journey. I just wanted it to be an honest legacy. And it was time. I don’t know how much time I have left. But I’ve got nothing to lose now.

Were the filmmakers showing you how the story was evolving and getting your permission to include very personal information?

We had a few fisticuffs. If it was something I really wasn’t going to be able to handle, we’d make adjustments. There are some things there I didn’t want in. But that doesn’t matter. That’s me still trying to protect something. When I look at it in the context of the film, I see what it means to the film. The film is totally unique. It’s brilliantly put together. I don’t have any gripes. There are parts of it that make me uncomfortable. I didn’t really have any say in it. Friendship and trust in them and knowing that they were doing a great job, once we were rolling, we were rolling.

One of the aspects of your career that the film talks about is your instant rise to fame. Were you prepared for that?

My idea of the future was the following Wednesday. I didn’t plan it and there wouldn’t have been time to plan it anyway. I just remember me standing at Newport [Folk Festival], at the foot of the stairs that went up to the stage, knowing I was going to be introduced, and I would sing two or three songs. My knees were knocking, and my legs were shaking, uncontrollably. I was so nervous. There was this massive response. The next day, it was press, and from there was TIME magazine and all that. I spent a lot of energy when I was young trying to do the right thing; not be commercial and not get horrible and not cut people off and all those things I’d heard about. That was my life. I loved that. I loved my own voice. I loved what came out. I loved the public—but that didn’t keep me from having horrendous stage fright. I just kept going. I knew I’d rather be called “the Madonna” than “the dumb Mexican.”

The Mexican side of your heritage is touched on only a little bit in the beginning of the film. Why is that?

My mom was from the British Isles so I did the early Scottish, Irish, and English folk songs. Late in the game, I thought, “Why didn’t I go to the Spanish stuff? That’s part of my heritage.” I’m sure it’s all tied to early childhood stuff. I don’t speak Spanish. I taught myself Spanish once and gave one press conference and then forgot all my Spanish. I did an album in Spanish [Gracias a la Vida], but I wasn’t immersed in being Latina.

You and Bob Dylan were together at the start of his career. In the film it looks like you were guiding him. We see a very different Dylan than we have before.

The period of time when Bob and I were traveling together, singing together, it was just wonderful. We knew it was a slam dunk every single night, that people were going to be ecstatic. And we’d be silly. I don’t know how long that lasted. But we were everything that you saw on screen. I’d never even seen that footage. Seeing him in this other light is just a real treat.

You performed at the March on Washington [including with Dylan]. What was the experience of hearing Dr. Martin Luther King Jr. speak like for you?

There are times when you know what’s going on is exceptional. It was a hot day. There were 350,000 people. I’d never seen that many people in my life. I had worked with SCLC [Southern Christian Leadership Conference] and King’s people. I had already been in Grenada, Mississippi and walked the children to school. Then came this day. When King spoke and he put the notes down and gave that speech, I was never the same afterwards. That happened to a lot of us.

These days, artists have more power, more reach, more impact than ever before, yet it feels like they have less courage. As someone who is an activist and using your platform to be fearlessly outspoken about issues, what are your thoughts about that?

The key is in one’s ability to take risks. That’s the hardest thing. It was what I was willing to do, and the people around me were willing to do. Some people now are willing to do that, but it’s not an atmosphere that’s conducive to that. We’re living in the age of bullies, hatred, fear and fascism. In that context, how do you find the right group? We don’t have the glue we had in the ‘60s, either. It’s dispersed all over the place. I would really encourage people to find one of those places that they relate to and just be a part of it, whether you want to give money or volunteer or lick stamps or become active or finally take a risk. Without that risk, we’re not going to make any real social change.

In the film, you said you were “addicted to activism.” What does that mean to you?

It was awful to say, and it was awful to realize. Why am I going off to Cambodia when I could be spending time with my kid? I couldn’t. It was the early stuff that wrecked that for me. It was intimacy. I couldn’t be present when I needed to be present, even if I was standing there. I guess I felt safest when I was taking care of somebody else’s kids.

It doesn’t take away from the emotional part of why I wanted to be there, and being present when I was there, and doing the things that I did, which I think were good. I think they were well-guided and used me in the best possible way. Used me for the right thing and I’m fine with that.

Were your intimacy issues ever resolved?

It’s not clear in the film, but I resolved it by not going into it. The last few months with my therapist who took me through all that stuff was, “Now that we got all this under your belt and you’re right with yourself, it’s time to find a partner.” I thought, “I got this far. It feels wonderful. I feel whole. Why screw it up?” I live on a compound so I’m not all by myself by any means, that would be different if I were. But I am living with myself really quite well.